The architectural career of my father, Habib Rahman, in Calcutta began with death. In 1947, shortly before independence, he was appointed Senior Architect in the Bengal PWD (Public Works Department). His first project was the memorial to Mahatma Gandhi at Barrackpore, north of Calcutta on the Hooghly. One of the first Indians to graduate in architecture from the USA (MIT, 1944), he had studied and worked with Walter Gropius, Konrad Wachsmann and Ely Kahn. His high-modernist Bauhaus background did not serve him well, however, when conceiving and designing this first memorial to Gandhi after his assassination. Inspired more by Frank Lloyd Wright, Rahman developed a contemporary shikhara-like form in cast concrete, combining abstracted elements from Islamic, Hindu and Christian architecture, yet trying hard to avoid any sense of pastiche.

Gandhi Ghat was inaugurated in January 1949 by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, who reacted ecstatically to the design. Asking to meet the architect, he questioned Rahman closely on his background and decided to shift him to the Central PWD in Delhi. The meeting with Nehru transformed Rahman’s life, especially in his design philosophy. That first ringing endorsement of his attempt to make a structure that was wholly contemporary yet reached out to our cultural traditions, would keep surfacing in Rahman’s work – each time under nudging from Nehru.

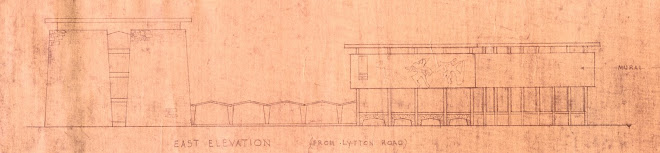

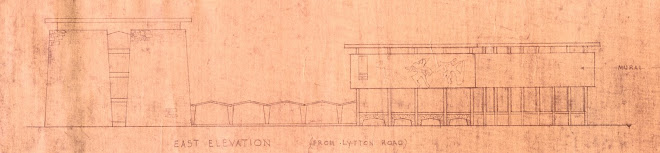

In Delhi, in the early 1950s, Rahman plunged into designing buildings for the institutions of the modern nation-state, many concentrated in the Indraprastha (ITO) zone. Maulana Azad, senior Congress leader and Minister of Education, conceived the three state cultural bodies, the Lalit Kala Akademi, Sangeet Natak Akademi and Sahitya Akademi, in 1952. Nehru awarded the Padma Shri to Rahman in 1955, for Gandhi Ghat and other buildings in Calcutta and Delhi. When Azad died in 1958, Nehru called Rahman to design his tomb. Another memorial to death, this was Rahman’s first project to be constantly vetted by Nehru as it was conceived and evolved. A thin-shelled concrete cross-vault structure was developed rhyming the arch of the eastern gateway of Shahjahan’s great Jama Masjid, which formed the backdrop. Even as this was being finished in 1959, Rahman was designing the offices, galleries and theatre for Azad’s Akademis in a corner plot at the Mandi House circle. To be called Rabindra Bhavan in memory of Tagore, it was to be finished in time for Tagore’s birth centenary year in 1961. The Lalit Kala Akademi, under Humayun Kabir, hosted a national seminar on architecture in 1959, at Jaipur House. The inaugural address was by Jawaharlal Nehru, probably the only ‘ruler’ in Delhi to have had as great an impact on the architecture of his times and his city since Shahjahan.

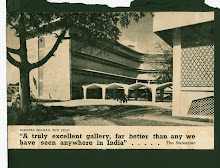

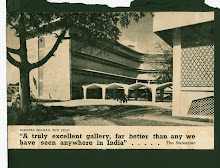

New Delhi being a necropolis, the plot earmarked for the Akademis’ building complex had a small ruined mosque and graves on it. Designing around that, Rahman’s first plan, a dry institutional one, was instantly rejected by an irritated Nehru. He directed him to go back to the Gandhi Ghat and Maulana Azad memorials, and to reflect the philosophy of Tagore in this building, which was to be a premier symbol of the culture of new India. Evolving a design idiom on an institutional scale from those early projects was a struggle for Rahman, for both the earlier examples Nehru liked were symbolic memorials, and small, singular structures. Under the prodding of Nehru, he finally came up with the concepts for the three buildings to be built, carefully incorporating the ruined mosque between the gallery building and the offices of the Akademis. Again, Nehru loved the result.

While the Azad arch was a tribute to the Jama Masjid arch, the sloping stone walls in the Lalit Kala ensemble were a tribute to Delhi’s Tughlaq buildings, many of them tombs, and then still easily visible across yellow mustard fields all over Delhi. Jalis in cast cement were extensively used for the first time. The spiral and cantilevered stairs, interior handrail, and light and skylight details were carefully thought out to create an open, airy gallery space.

Rabindra Bhavan was a huge success after its opening, but the theatre block remained to be built (and never was). The lessons Rahman learned from this exercise also influenced his close friend, Joseph Stein. The buildings that followed in Delhi after Rabindra Bhavan, marking the landscape of the capital in the 1960s and 70s, were completely different from the Bauhaus blocks of the 1950s.

When Nehru died in May 1964, we watched his funeral procession from the roof of the School of Planning at ITO, going past two Rahman buildings under construction: Indraprastha Bhavan and the WHO headquarters. In many ways, this symbolised the end of the Nehruvian dream. The war with China had already happened and snapped the spirit of the new nation. The visionary energy of the first decade of independence, where the state was the most important patron, was dissipating.

By the time my father died in December 1995, on his bed under his 1961 photograph of Rabindra Bhavan, that India was long gone. Indian architecture had by then produced two generations of engaged and thoughtful practitioners, nowhere more than in the city of Delhi. A remarkable collection of modernist buildings had been built, starting with that early push from Nehru. But then came the emergency and entire areas of old Delhi were destroyed. A new politics of fear and hate were the new mantra, and Ayodhya in December 1992 changed everything forever. It was remarkable how a single building and its effacement transformed a nation’s psyche. By 1995, market forces were the new god. A glass-and-steel Gurgaon had come up overnight on fields with no water or electricity or sewage.

When I stand in Rabindra Bhavan now, on the mound where the mosque arches with their finely etched calligraphy in plaster stood by the quiet graves, there is a slick sculpture garden ringed in three tiers of hard-edged granite. The gallery building is torn apart, to be clad in new gleaming marble and glass, like that in Gurgaon. The Lalit Kala officials of today, ashamed of guiding foreign ambassadors through their gallery, will build a lift tower next to those old bones lying not far below. Their memory has been effaced, and I guess Nehru’s attempt to memorialise Tagore and his vision of a modern Indian culture in the heart of Delhi will also soon join those graves in the earth.

Ram Rahman, November 2008 (First published in the catalog for Nature of the City, December 2008, curated by Alexander Keefe and Nitin Mukul, Arts i Gallery, New Delhi)

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Nehru at the Inauguration of Gandhi Ghat

Gandhi Ghat Barrackpore, 1949, Habib Rahman

Maulana Azad Mazhar, 1959

May, 1961, Rahman explains plan details to Nehru

Nehru's Body going past the Indraprastha building and WHO under construction at ITO, both designed by Rahman. Photo from the top of the School of Planning by Habib, May, 1964

Habib Rahman on his deathbed, Dec 19, 1995

Nehru at the Inauguration of Gandhi Ghat

Gandhi Ghat Barrackpore, 1949, Habib Rahman

Maulana Azad Mazhar, 1959

May, 1961, Rahman explains plan details to Nehru

Nehru's Body going past the Indraprastha building and WHO under construction at ITO, both designed by Rahman. Photo from the top of the School of Planning by Habib, May, 1964

Habib Rahman on his deathbed, Dec 19, 1995