Friday, December 12, 2008

Letter to Ambika Soni, Minister of Tourism and Culture

Minister of Tourism and Culture

R/No. 501, C Wing, Shastri Bhawan

New Delhi

September 15, 2008

Ref : Renovation of the Rabindra Bhavan Gallery, Lalit Kala Akademi

Dear Ambikaji,

I have heard some alarming reports on the renovation work now ongoing at the Rabindra Bhavan Gallery. It was designed by my father Habib Rahman when he was a senior architect in the CPWD. The design evolved between 1959 and 1961 in direct consultation with Jawaharlal Nehru. As a memorial to Tagore, Panditji was particularly concerned that it reflect the ideals of Gurudev, and was very pleased with the final result.

The building is regarded as one of the finest examples of Indian Modernism, particularly one built by the CPWD which was not known for innovation. It has been the best gallery space in India, unmatched till today, and has seen two generations of Indian artists show their best work there.

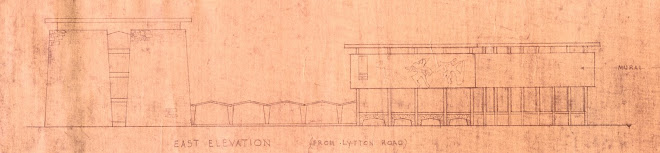

While no one would object to upgrading the building, the artists commu¬nity has become alarmed at what seem to be drastic alterations which will destroy the design integrity and philosophy of the building. The neutral cement-tile flooring has been torn out and there seems to be a move to replace it with marble. No gallery in the world uses an expensive material like that which is totally unsuited to the needs of contemporary art. There are also unconfirmed reports that in order to add a lift to comply with disabled access, a separate lift shaft is to be built outside the exhibition block between the gallery and the Akademi block. This would be a total violation of the de¬sign integrity of the complex. There is also a proposal to punch through the facade on the Mandi House Circle side and put a glass wall there.

Both these proposals would be shocking changes to a historic structure. It is my belief that our Modernist buildings, of which Delhi has a distinguished collection, are as worthy of preservation as the Qutub and Humayun’s tomb complex or the Lutyens zone buildings.

If indeed these are the major changes underway, I appeal to you to set up a small com¬mittee of architects and artists to sit down and advise on the upgradation, which can cer¬tainly be done without permanently damaging the design of the complex. It is imperative that artists who actually use the space have a say in what is done to make it better suited to the needs of current practice.

Disabled access can easily be accomodated with modern stair rail lifts and small interior platform lifts. I also appeal to the Ministry and Akademi to retain the details such as the stair railings. I have also proposed for many years that the many skylights of the original plan be reopened to allow the illumination of the galleries with the indirect light which was a special feature of the space for many years.

I am enclosing some photographs and pieces from the professional press on the building which have appeared over the years.

With regards,

Ram Rahman

CC: Sonia Gandhi

SK Mishra, OP Jain, INTACH

KT Ravindran, DUAC

Sitaram Yechury, Chairman, Parliament Subcommitte on Culture

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

Mail Today, November 28, 2008

A makeover that’s getting a bit messy | ||

by Archana | ||

IN AN open letter to the minister for tourism and culture, Ambika Soni, artist/ photographer Ram Rahman has asked for clarifications on the ongoing renovation of Rabindra Bhawan. “ I think it would be fitting for the ministry and the Lalit Kala Akademi to make public its plans for structural additions to the building and also to clarify if these plans have been approved by all the civic authorities which have jurisdiction over New Delhi, including the Delhi Urban Arts Commission ( DUAC),” Rahman says in the letter. It is also addressed to S. Jaipal Reddy, minister for urban development, Ashok Vajpeyi, chairman, Lalit Kala Akademi, DUAC chairman K. T. Ravindran and Akademi secretary Sudhakar Sharma. A copy of the letter has also been marked to UPA chairperson Sonia Gandhi and CPI( M) politburo member, Sitaram Yehchury, who is on the parliamentary sub- committee on culture. Ravindran, an architect, incidentally, is a part of the team overseeing the renovation project. Vajpeyi expresses surprise at the dust being raised on the issue. “ It is a housekeeping exercise, so where’s the need to discuss the matter in public?” he asks. “ The Rabindra Bhawan’s galleries are being restored because the building has been around for a very long time and has to be upgraded. Its electric wiring and other facilities are outdated,” he says. The Bhawan, whose foundation stone was laid by the then president, Rajendra Prasad, in April 1959, was designed by Rahman’s father, architect Habib Rahman. Vajpeyi said that no structural changes were being made, so the integrity of the original plan was being maintained. “ I feel the objection to the renovation is an over- reaction,” he says. Rahman reacts by describing it as a “ sordid story”. He points out that he wrote the first letter to Soni on September 15 because he was alarmed at the way the whole place was being torn apart. “ The floor was being changed unnecessarily. They said Kota stone was being used and I freaked out. Two days later, I was told they would put marble. I freaked out more. Now I do not know if they are using marble or not,” Rahman says. He points out that marble was a ridiculous idea because it’s “ the softest stone” and gets damaged easily. “ No gallery in the world uses marble. But I still see marble lying outside,” he says. Vajpeyi clarifies that although some people were not completely opposed to marble, “ I decided against using it. Now we’re going to have a wooden floor, which is the norm all over the world.” Rahman is also upset about the Akademi’s plan to install a lift shaft. In his letter, he had pointed out that the community of artists had become “ alarmed at what seems to be drastic alterations which will destroy the design integrity and philosophy of the building.” VAJPEYI says an elevator will make the building disabled and senior citizen- friendly. “ When we had Mr Jaipal Reddy for one of our shows, we couldn’t take him to the upper levels. We’ve also been receiving notices from the MCD to make the building disabledfriendly.” The renovation work being carried out by the National Buildings Construction Corporation should get over by December- end, in order to be ready for a big Mexican art show scheduled for January. “ We are not just losing revenue but also delaying opportunities to people from outside who come to us for their shows,” Vajpeyi says. Rahman insists “ the minister knows nothing about what is going on.” To this, Vajpeyi retorts, “ We are not a subsidiary of the ministry but an autonomous body. We consult them only on major issues but don’t bother it for matters of general interest.” Vajpeyi’s final word on the debate? “ I am not aware of any debate in the art circles,” he says. Rahman, though, is in no mood to let it pass. archana. khare@ mailtoday. in |

Tagore, Nehru, Rahman

Gandhi Ghat was inaugurated in January 1949 by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, who reacted ecstatically to the design. Asking to meet the architect, he questioned Rahman closely on his background and decided to shift him to the Central PWD in Delhi. The meeting with Nehru transformed Rahman’s life, especially in his design philosophy. That first ringing endorsement of his attempt to make a structure that was wholly contemporary yet reached out to our cultural traditions, would keep surfacing in Rahman’s work – each time under nudging from Nehru.

In Delhi, in the early 1950s, Rahman plunged into designing buildings for the institutions of the modern nation-state, many concentrated in the Indraprastha (ITO) zone. Maulana Azad, senior Congress leader and Minister of Education, conceived the three state cultural bodies, the Lalit Kala Akademi, Sangeet Natak Akademi and Sahitya Akademi, in 1952. Nehru awarded the Padma Shri to Rahman in 1955, for Gandhi Ghat and other buildings in Calcutta and Delhi. When Azad died in 1958, Nehru called Rahman to design his tomb. Another memorial to death, this was Rahman’s first project to be constantly vetted by Nehru as it was conceived and evolved. A thin-shelled concrete cross-vault structure was developed rhyming the arch of the eastern gateway of Shahjahan’s great Jama Masjid, which formed the backdrop. Even as this was being finished in 1959, Rahman was designing the offices, galleries and theatre for Azad’s Akademis in a corner plot at the Mandi House circle. To be called Rabindra Bhavan in memory of Tagore, it was to be finished in time for Tagore’s birth centenary year in 1961. The Lalit Kala Akademi, under Humayun Kabir, hosted a national seminar on architecture in 1959, at Jaipur House. The inaugural address was by Jawaharlal Nehru, probably the only ‘ruler’ in Delhi to have had as great an impact on the architecture of his times and his city since Shahjahan.

New Delhi being a necropolis, the plot earmarked for the Akademis’ building complex had a small ruined mosque and graves on it. Designing around that, Rahman’s first plan, a dry institutional one, was instantly rejected by an irritated Nehru. He directed him to go back to the Gandhi Ghat and Maulana Azad memorials, and to reflect the philosophy of Tagore in this building, which was to be a premier symbol of the culture of new India. Evolving a design idiom on an institutional scale from those early projects was a struggle for Rahman, for both the earlier examples Nehru liked were symbolic memorials, and small, singular structures. Under the prodding of Nehru, he finally came up with the concepts for the three buildings to be built, carefully incorporating the ruined mosque between the gallery building and the offices of the Akademis. Again, Nehru loved the result.

While the Azad arch was a tribute to the Jama Masjid arch, the sloping stone walls in the Lalit Kala ensemble were a tribute to Delhi’s Tughlaq buildings, many of them tombs, and then still easily visible across yellow mustard fields all over Delhi. Jalis in cast cement were extensively used for the first time. The spiral and cantilevered stairs, interior handrail, and light and skylight details were carefully thought out to create an open, airy gallery space.

Rabindra Bhavan was a huge success after its opening, but the theatre block remained to be built (and never was). The lessons Rahman learned from this exercise also influenced his close friend, Joseph Stein. The buildings that followed in Delhi after Rabindra Bhavan, marking the landscape of the capital in the 1960s and 70s, were completely different from the Bauhaus blocks of the 1950s.

When Nehru died in May 1964, we watched his funeral procession from the roof of the School of Planning at ITO, going past two Rahman buildings under construction: Indraprastha Bhavan and the WHO headquarters. In many ways, this symbolised the end of the Nehruvian dream. The war with China had already happened and snapped the spirit of the new nation. The visionary energy of the first decade of independence, where the state was the most important patron, was dissipating.

By the time my father died in December 1995, on his bed under his 1961 photograph of Rabindra Bhavan, that India was long gone. Indian architecture had by then produced two generations of engaged and thoughtful practitioners, nowhere more than in the city of Delhi. A remarkable collection of modernist buildings had been built, starting with that early push from Nehru. But then came the emergency and entire areas of old Delhi were destroyed. A new politics of fear and hate were the new mantra, and Ayodhya in December 1992 changed everything forever. It was remarkable how a single building and its effacement transformed a nation’s psyche. By 1995, market forces were the new god. A glass-and-steel Gurgaon had come up overnight on fields with no water or electricity or sewage.

When I stand in Rabindra Bhavan now, on the mound where the mosque arches with their finely etched calligraphy in plaster stood by the quiet graves, there is a slick sculpture garden ringed in three tiers of hard-edged granite. The gallery building is torn apart, to be clad in new gleaming marble and glass, like that in Gurgaon. The Lalit Kala officials of today, ashamed of guiding foreign ambassadors through their gallery, will build a lift tower next to those old bones lying not far below. Their memory has been effaced, and I guess Nehru’s attempt to memorialise Tagore and his vision of a modern Indian culture in the heart of Delhi will also soon join those graves in the earth.

Ram Rahman, November 2008 (First published in the catalog for Nature of the City, December 2008, curated by Alexander Keefe and Nitin Mukul, Arts i Gallery, New Delhi)